Isopods in the Forest

Woodlice have been on the planet far longer than human beings, with some scientists believing that these small invertebrates roamed the earth 100 million years ago. Since then, woodlice have been a familiar sight in human history. It is believed that in the past humans used to keep a small pouch containing woodlice around their necks, swallowing some when experiencing a stomach-ache. This may have been due to the calcium carbonate found within the exoskeletons of woodlice, which would have helped neutralise stomach acids.

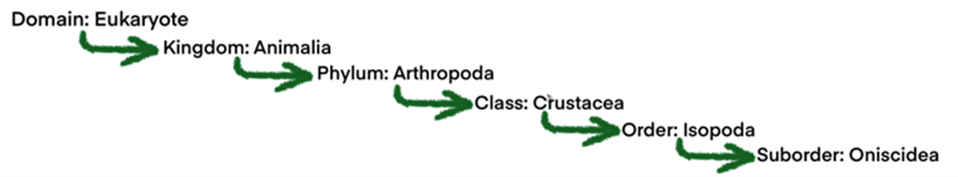

Woodlice are often mistaken as insects, related to other invertebrates such as beetles and bugs. This is a misconception, as woodlice are members of the class Crustacea- making them crustaceans! Woodlice are more closely related to crabs, lobsters, and shrimps than terrestrial insects.

Woodlice are from the order isopoda, which contains around 10,000 species worldwide. In the isopod order there is a species known as the giant isopods, which are aquatic ancestors of the common woodlice. Since evolving from these ancestors, around 3,500 species have been discovered so far. 37 of these species reside within the British Isles.

Despite living on this planet before our time, woodlice have an incorrect reputation as pests due to wondering into our homes and gathering in areas of damp. As a matter of fact, the benefit of woodlice outweighs the damage they do to our homes and environment.

In this article you will learn how to identify some of the most common woodlice, and why these small crustaceans shouldn’t be considered pests anymore

Anatomy

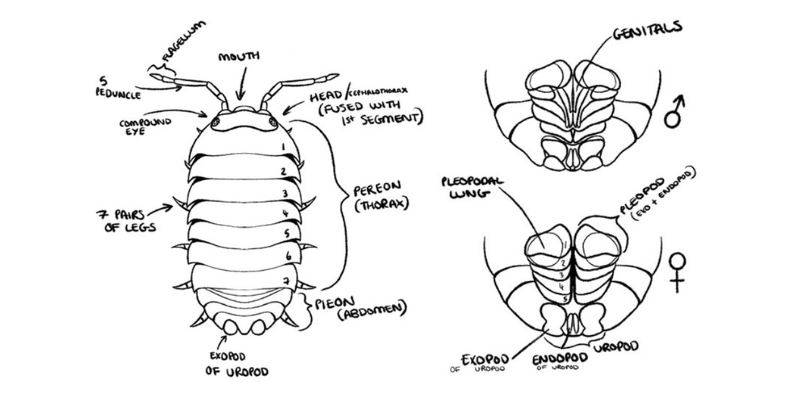

Woodlice are split into two parts, the pereon (thorax) and the pleon (abdomen).

The pereon is made up of seven segments, with the first segment being fused with the head. Each segment has a pair of legs attached to it, meaning that woodlice have seven pairs of legs in total.

As mentioned previously, woodlice are crustaceans, meaning that these invertebrates need water to survive. This is where the pleon comes into use. The pleon is made up of 5 segments, and on the underside of the pleon are gill like structures called pleopods. Pleopods move, like gills, to trap water underneath and allow movement of oxygen. Some woodlice have modified ‘pseudo-trachea’ on these pleopods, increasing the surface area to take up even more oxygen. These are found on more inland and well-adapted species.

Another anatomical feature is that woodlice have long antenna that have unique ends to them (flagella).

When identifying a woodlouse, you look at numerous features such as the exoskeleton colour, number of pleopodal lungs, flagella type and behaviour.

Life Cycle

There are four stages to a woodlouse’s life:

- Egg stage. Adult female woodlice carry around 25-90 fertilized eggs in a small fluid-filled pouch under their bodies. When hatched, these young will stay in this pouch until they are big enough to survive in the wild. This takes around 40-50 days.

- Baby (manca): Even though the baby woodlice (manca) are big enough to leave the pouch, they are technically not fully developed. When released from the brood pouch, the woodlice only have six pairs of legs. Within 24 hours of release, these woodlice will go through a first moult, gaining their seventh pair of legs.

- Juvenile.

- Adult: Woodlice are expected to live about two to three years at this stage.

‘Famous 5’ Woodlice

Armadillidium vulgare (the common pill woodlouse)

How to identify:

- Length: 18mm.

- Colour: Uniform slate grey, pink or brown. Mottled patterns can be found around coastal areas.

- Number of pleopodal lungs: Two.

- Flagella: Two segments.

- Behaviour: Rolls into a perfect sphere when disturbed.

Habitat

A generalist species, found in natural and man-made sites. Extremely common in the south and east of England, restricted to coastal and man-made sites in the north and west, and is absent from central northern England.

Oniscus asellus (the common shiny woodlouse)

How to identify:

- Length: 16mm.

- Colour: Very shiny and grey with two rows of yellow patches along the outside of the pereon.

- Number of pleopodal lungs: None.

- Flagella: Three segments.

- Behaviour: Initially remains motionless when disturbed, runs quickly when continuously provoked. May be difficult to pick up due to its flattened body and smooth surface. Does not roll up into a ball.

Habitat

A generalist species, found in all damp habitats. Especially common under bark and rotting wood in deciduous woodlands. Extremely common across throughout the British Isles.

Porcellio scaber (the common rough woodlouse)

How to identify:

- Length: 17mm.

- Colour: Slate grey, with a dull, rough look to the exoskeleton.

- Number of pleopodal lungs: two pairs.

- Flagella: Two segments.

- Behaviour: Initially remains motionless but runs away quickly when disturbed. Does not roll into a ball.

Habitat

A generalist species, found in a variety of habitats throughout Britain and Ireland. It prefers drier conditions compared to other common species (such as Oniscus asellus), so is often found within compost heaps.

Philoscia muscorum (the common striped woodlouse)

How to identify:

- Length: 11mm.

- Colour: Shiny mottled brown with a dark central stripe.

- Number of pleopodal lungs: None.

- Flagella: Three segments.

- Behaviour: Runs extremely fast when disturbed and feels soft to the touch when attempted to be picked up.

Habitat

A generalist species, found in hedgerows and grasslands. This woodlouse is often hidden at the base of grass tussocks. Common through Britain and Ireland.

Trichoniscus pusillus (the common pygmy woodlouse)

How to identify:

- Length: 5mm.

- Colour: Purplish-brown or reddish-brown.

- Number of pleopodal lungs: None.

- Flagella: One distinct conical section that tapers to a point.

- Behaviour: Runs rapidly when disturbed.

Habitat

A generalist species, found in damp soil and damp leaf litter. It is very common and found throughout the British Isles.

Importance of woodlice

Woodlice rarely destroy living plants, instead preferring to eat vegetation that has begun to die and decompose. This includes decaying leaf litter and rotting wood. Due to this, woodlice are key factors in an ecosystem. Woodlice munch on dead plants, breaking down the vegetation into smaller fragments that as deposited back into the ground as faecal pellets. This allows more rapid decomposition by bacteria and fungi, returning nutrients back into the soil and supporting new vegetation growth.

Scientists also believe that woodlice may graze fungal hyphae (structures that support fungal growth) off leaves, supporting overall tree health.

Finally, woodlice are a food source for a variety of species, such as toads, centipedes, and other larger invertebrates. One species, known as the woodlouse spider, preys exclusively on woodlice.

How you can help

As woodlice rely on high moisture and a cool temperate, you can hunt through decaying matter in autumn and identify some of these woodlice above. If found, you can report your findings to the Forest or directly to the British myriapod and isopod group at https://bmig.org.uk/. This group’s mission is to educate the public on these invertebrates, and monitor the species across the country, which you can help support.